Eliminating Water Contamination in Air Systems

By Michael Schapoehler, Product Technology Manager, Airline Hydraulics Corp.

In the dog days of summer, people often say, “It’s not the heat, it’s the humidity.” This is true – on a hot day, it’s often the humidity that makes us suffer most. Unfortunately, pneumatic machinery also suffers from an increased likelihood of water in its air lines.

How water forms in air lines

One of the most prominent triggers for excess water in pneumatic air lines is an increase in temperature. When temperatures rise, water evaporates and increases humidity, meaning there is a higher amount of water particles in the air. Since pneumatics rely on this air, it’s not surprising that systems release a significant amount of water during the hotter months. In fact, a 25-horsepower compressor can release more than 18 gallons of water in one day during the summer.

Another trigger for excess water in an air line is fluctuation in air temperature. If the air temperature drops lower than its dew point (the atmospheric temperature at which water droplets can condense), water vapor condenses to form water. At this point, the relative humidity has essentially reached 100%. A typical example of this phenomenon is when, on a hot day, droplets form on a glass with cold drink.

The same thing happens in pneumatic systems. Temperature fluctuations in day-to-day operations, or throughout the system itself, could potentially cause a similar “dew” to form within the system. If the air is carrying water vapor and goes from hot to cold within the line, vapor will condense to form water that will likely accumulate throughout the system.

It is a natural occurrence for water to be present in the air and fluctuate between its gas and liquid states. So why is it so harmful to pneumatic processes and machinery?

Why water must be removed

Even a small amount of water within a pneumatic air line can result in big issues. Here are a few problems that occur when excess moisture goes unchecked.

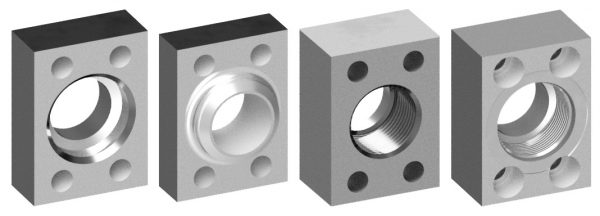

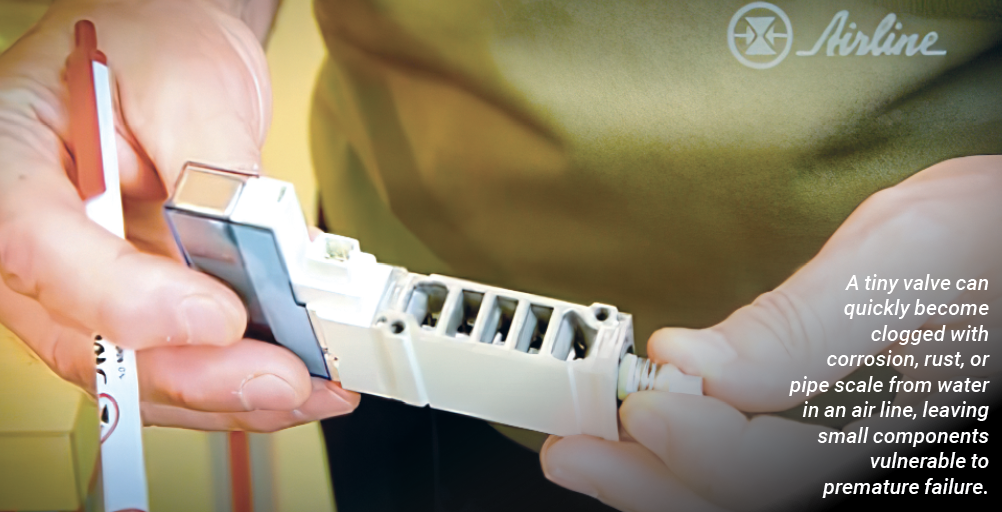

Loss of component lubrication. Pneumatic components are prelubricated at the factory. Water in a compressed air system compromises this lubrication and even has the potential to wash it away entirely. Unfortunately, many components rely on this lubrication to function correctly; without it, they are subject to premature wear and failure. It does not take much water to wash away the lubrication from smaller valves typically found in pneumatic systems. Within these components, rubber seals are prone to swelling, stiffening, and deterioration when subject to moisture.

Bacterial growth. This moisture can also lead to the growth of bacteria and microorganisms in pipes and components. Some of these organisms can survive and multiply in higher temperature ranges, such as 45°C to 90°C (113°F to 194°F); others need lower temperatures, ranging from 25°C to 40°C (77°F to 104°F). However, the one thing they all need is moisture. Pneumatic lines can become breeding grounds for bacteria and mold that can gunk up components and cause health and safety concerns.

Pipe scale and rust. Moisture also wreaks havoc on piping through the formation of pipe scale and rust. This buildup accumulates to decrease the pipe’s interior surface area, which increases the pressure loss as air passes through and reduces the system’s overall performance. Over time, the pipe scale and rust detach from the piping, traveling through the pneumatic system and causing further issues.

Pneumatic components are intricate, precise, and relied on to make a pneumatic system run properly. When components become clogged with debris, a machine cannot operate at full capacity and may even fail completely. It may require shutdown to assess which component is failing and to then replace that component.

Poor air quality for important processes. When compressed air is used directly in a product or process, it’s even more critical to remove moisture and its byproducts like bacteria, rust, and debris. In the simple process of cleaning parts and products using a blowgun, for example, a moist blast of air could carry rust, mold, and bacteria.

Another process sensitive to the effects of water, bacteria, and particulate is a paint booth. Paint is precisely mixed with other chemicals to provide an aesthetic and protective coating to a product. If the pressurized air used to apply this finish is compromised, the impurities adversely affect its color, adherence, and quality. The painted item would be less protected from the elements and possibly suffer from premature wear. These are just two common processes that suffer from poor air quality, but there are many more depending on the application and industry.

Increased costs. For original equipment manufacturers and machine builders, it’s costly to assume the end user will have clean, dry air flowing through the system. This assumption often results in premature wear and breakdown of the machine, which leads to increased time and resources to travel to the facilities, troubleshoot, and service the machines.

End users need clean and dry air because they rely on the machine to operate without problems; their income often depends on it. At best, water damage will cause unplanned work stoppages to replace damaged components. At worst, it creates long downtimes to troubleshoot, source and purchase components, or get the machine serviced. If portions of the final product come into contact with moisture and debris from compressed air, latent damage and quality issues can occur. These scenarios all lead to reduced profits, which is especially harmful to businesses running off thin margins.

Removing water

Here are a few best practices to decrease or prevent moisture accumulation.

Drain the air compressor. Air compressor tanks often contain a drain at the bottom so that collected water can be released. Be sure to drain the tank after each use of the air compressor to prevent a consistent buildup of water. Drain the air compressor regularly, especially during the hotter months. If the air compressor is continuously under high demand, empty the tank frequently.

Create consistent temperatures. Pay attention to differences in temperatures within the system. Water vapors turn into liquid water when passing from a warmer to a colder area. Knowing this, design a pneumatic system to avoid these temperature changes.

For example, air compressors are noisy, so designers may put them outside or in a non-temperature-controlled room away from the rest of the system. During the hotter months, that compressor delivers hot compressed air to cold indoor areas. This setup is a recipe for condensation since warm air is running through cool pipes. By placing the air compressor in a similarly temperature-controlled room, the condensation may significantly reduce.

Choose pipe material wisely. As noted earlier, water wreaks havoc on air piping and creates rust and scale. Carefully select pipe material to reduce these risks. Some materials, such as steel, are prone to rust and scale. Other materials, such as marine-grade aluminum pipes, are more resistant to rust and help prevent oxidation-based contamination. Implementing a piping system with cleaner interior surfaces decreases issues related to moisture buildup and increases smooth, laminar airflow.

Adjust piping direction. As water vapor condenses and becomes liquid, it typically collects and pools at the bottom of the pipe. One way to prevent this water from entering the rest of the system is to adjust where other pipes connect to the main line. Connecting these pipes to the top of the air line instead of the bottom, where the water collects, is likely to provide dryer air into the rest of the system. This method does not eliminate water but helps minimize damage that could occur further down the line.

Products to remove water from air lines

If those best-practices aren’t applicable to a system or aren’t enough to prevent water accumulation, some products in the marketplace can help remove excess water.

Filter/regulators. A filter/regulator solution reduces water and debris. The AW30 by SMC works well if the system has high air flow. The AW30 uses a cyclone-effect to spin the air at high speeds, forcing the water and debris to the sides of the unit, where it becomes separated and drains out the bottom. This cyclone-effect does require a high amount of air pressure, so if this pressure is lacking, consider a different solution, such as a water separator.

Water separators. Water separators come in a range of sizes to remove water from pneumatic lines. Smaller ones are good for point-of-use, and larger ones can serve as mainline filters. They are one of the most economical options for removing water from air lines.

Air dryers. Air dryers are another option for keeping water out of pipes. Air dryers can help a large facility experiencing water throughout its air lines. Air dryers exist for more significant water removal issues, such as widespread rusting and corrosion of lines, water spots from air tools, and liquid coming from hoses and lines.

There are two types of air dryers – desiccant and refrigerated. For refrigerated dryers, water condenses through the use of cooling temperatures, much like a refrigerator. As wet air comes into contact with the dryer, it is significantly cooled down, which turns the water vapor into liquid water that goes into a water-trap. Then the cold air heats back to room temperature, resulting in dryer air. A refrigerated air dryer works like a dehumidifier.

Desiccant air dryers use absorptive materials, such as silica gel, to absorb the water vapor in the lines. The vapor then turns to liquid and sticks to the contents until they are cleaned out. With any air dryer, it’s essential to make sure the air pressure and capacity fit the compressor.

Water in pneumatic air lines causes many issues that can affect a business’s efficiency and bottom line. Implementing these cost-effective best practices and products can help achieve clean and dry air during every season, including the hot and humid months. For help determining which solution is most useful, consult with a professional to determine the best option for a system’s water removal needs.