Effects of Grease on Rotary Shaft Seals

Less than 20% of seals and gaskets ever reach their expected “operating life” in any given application. Of the 80% that are replaced due to scheduled maintenance, ineffective performance, or failure, 40% can be attributed to improper lubrication. With the steady rise in the price of raw materials, it is imperative that companies continue to examine ways to increase the life of seals and related mechanical products. This can increase machine uptime, reduce labor costs for repair technicians, and reduce the cost of replacing seals, gaskets, and related mechanical components. Effective use of lubricating grease is one variable that will contribute to maximizing the life of a seal in a rotating shaft application. This article will discuss understanding the types and functions of grease; the interaction of the shaft seal lip in a dynamic rotating application; effective greasing requirements; and indications of failure or reduced performance between the grease and a seal lip.

Less than 20% of seals and gaskets ever reach their expected “operating life” in any given application. Of the 80% that are replaced due to scheduled maintenance, ineffective performance, or failure, 40% can be attributed to improper lubrication. With the steady rise in the price of raw materials, it is imperative that companies continue to examine ways to increase the life of seals and related mechanical products. This can increase machine uptime, reduce labor costs for repair technicians, and reduce the cost of replacing seals, gaskets, and related mechanical components. Effective use of lubricating grease is one variable that will contribute to maximizing the life of a seal in a rotating shaft application. This article will discuss understanding the types and functions of grease; the interaction of the shaft seal lip in a dynamic rotating application; effective greasing requirements; and indications of failure or reduced performance between the grease and a seal lip.

Lubricating grease is made by adding a thickening agent to either mineral-based or synthetic oil. These agents include metallic soap, urea compound, organophilic modified clay, and carbon black. Additives such as rust inhibitors, extreme pressure additives, and oxidation preventatives are also used to increase performance. Greases are applied to mechanisms that can only be lubricated infrequently and where a lubricating oil would not stay in position. They also act as sealants to prevent ingress of water and incompressible materials. Grease-lubricated bearings have greater frictional characteristics due to their high viscosity.

Sealing against foreign contaminants such as moisture and solid airborne particles is vital for maintaining equipment performance. Contaminants that pass by the seal and enter the sump cavity can severely damage bearings, gears, and other machine components. Properly applying grease to a system creates a fluid film between the seal lip and shaft that minimizes frictional forces as well as protects against these foreign contaminants. The proper film thickness to achieve optimum service life from a seal is unique for each system. Microscopic projections from the surface of the shaft, referred to as “asperities,” dictate the ideal thickness of the lubricating film. The fluid film between the surface of the shaft and seal lip should be the same thickness as the average asperity height.

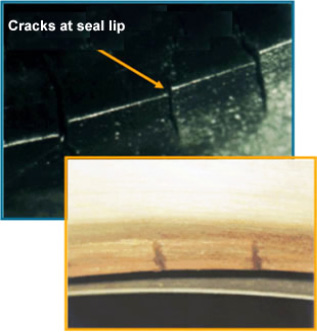

The reason moisture and solid particles will have significant adverse effects on a system is because water has a very low load-bearing capability, and if it is able to penetrate into the system, it will cause a degredation of the lubricating film. This breakdown will cause corrosive, adhesive, abrasive, and hydrogen-induced wear to the seal lip and casing. Solid particles allowed to enter the system will scratch and abrade surfaces, causing an increase in the amount of solid contaminants in the application. These “wear areas” provide ideal conditions for oxidation to occur. When the grease oxidizes, it typically darkens due to the build-up of acidic oxidation byproducts. These byproducts have a destructive effect on the grease’s thickening agent, as well as the seal lip material, causing softening, oil bleeding, and leakage.

The reason moisture and solid particles will have significant adverse effects on a system is because water has a very low load-bearing capability, and if it is able to penetrate into the system, it will cause a degredation of the lubricating film. This breakdown will cause corrosive, adhesive, abrasive, and hydrogen-induced wear to the seal lip and casing. Solid particles allowed to enter the system will scratch and abrade surfaces, causing an increase in the amount of solid contaminants in the application. These “wear areas” provide ideal conditions for oxidation to occur. When the grease oxidizes, it typically darkens due to the build-up of acidic oxidation byproducts. These byproducts have a destructive effect on the grease’s thickening agent, as well as the seal lip material, causing softening, oil bleeding, and leakage.

Proper grease application to the seal prior to installation is merely the first step in achieving full service life of a seal. Maintaining proper grease levels is equally important and is typically the area that is most neglected. A good rule to live by is no lip seal should run without lubrication for any prolonged period of time. This “dry-running” will cause the remaining grease to thin and eventually break down, resulting in direct contact between the shaft and seal lip. Overfilling is as detrimental to a system as dry-running. Overfilling will often cause a rapid rise in the internal temperature of a system caused by the increase in the amount of work the system must perform in order to push the excess grease out of the way. The most common method followed for proper greasing states the fill level should be approximately one quarter to one third of a seal casing’s free volume.

As is the case with seals, grease also has an optimum operating life. As the grease approaches the end of its ideal operating life, there are tell-tale signs that will warn an observant machinist that purging of the lubricant in the system is required. As we have previously discussed, when grease degrades, the lubricating film preventing surface-to-surface contact between the seal and shaft begins to deteriorate. As direct contact between the shaft and seal lip increases, a frictional phenomenon known as “Stick-Slip” begins to occur. “Stick-Slip” is a jerky motion between two surfaces due to alternating gripping and slipping of contact areas due to the lack of lubricating fluid. This action produces a surface wave oscillation that will literally tear a seal apart or, in a best-case scenario, allow leakage. Increased noise, as well as spikes in the internal temperature of an assembly are other key warning signs that should alarm the monitoring technician that lubricant levels are dangerously low.

With a full undersatnding of the relationship between the seal, shaft, and grease of an assembly, we are now able to center our attention on the risks and resulting costs of improper lubrication. Beyond the cost of having to replace a prematurely failed seal, we have also learned that this failed seal will often times allow foreign contaminants to enter the assembly. These contaminants will cause excessive wear on the internal components of a system, resulting in replacements needed for parts beyond just the sealing elements, as well as a need to replace the contaminated lubricant.

Understanding the relationship between the lubrication and sealing element of an assembly is vital to ensure resources are not being unnecessarily wasted. Selecting the proper seal for an application is as equally important as selecting the proper lubrication. Time is money, so do not allow costs to increase and profits to diminish because a decision was made without first consulting an expert in proper sealing procedures.