Fluid Power Companies Face Backlogs Due to Supply Chain, Labor Shortage

War in Ukraine could also impact sourcing.

By Michael Degan, Fluid Power Journal Editor

One day last month, 72 cargo ships waited to be unloaded at California ports, down from a peak of 109 on Jan. 9. Meanwhile, at the port of Charleston, South Carolina, 30 vessels waited for berths, according to a press report.

In recent months, sensational news photos have shown thousands of containers piled high and wide, waiting to be loaded onto trailers for delivery to destinations across the U.S. The photos, and other evidence, make it clear that the world’s supply chain is logjammed, affecting businesses around the world, including fluid power companies.

Fluid power firms are having problems filling orders, problems that in many cases have grown dramatically since the outbreak of the COVID pandemic in 2020. Besides the supply chain bottleneck, a hiring crisis is also making it difficult for fluid power companies to do business.

The shrinking numbers of ships waiting at California’s ports seems to indicate that the supply chain gridlock is easing, at least concerning sea freight. Still, most economists believe it will be 2023 before the supply chain is back to normal.

Now a new wrinkle may add to the supply chain logjam: the war in Ukraine.

Fluid power companies are reporting extended lead times to deliver their products amid a growth in sales.

“Our lead times have gone out quite long, partially due to the supply chain,” Paul Johnson, president of Aggressive Hydraulics, told Fluid Power Journal. “We have an abundance of orders. We’ve never had as many orders as we have now. I think that holds true with anyone in manufacturing these days. We can’t blame it on our supply chain 100%.”

Johnson said he’s seen pent-up demand since COVID struck in 2020, and that demand only grew in 2021. This year the company has about five times as many orders as they’ve ever had.

“We’re much more limited on what we can do there because of the supply chain,” Johnson said. “We can’t pull something in on a short turnaround basis when the material is six months or more out.”

It’s required flexibility to meet the demand.

“We’ve had to do some things differently in order to obtain the required lead times for some customers and industries,” Johnson said.

Adapting to shortages

Some companies have found ways to adjust to the supply shortages. Kim Harper-Gage, COO for North America at Festo, said the company uses technology and other methods to accommodate the lack of components.

“We are monitoring our logistics, our trucking, and our ocean freight in a very different way,” Harper-Gage told Fluid Power Journal. “And the visibility has really helped us be more agile and more responsive to those circumstances.”

Festo has adjusted how it manages inventory, taking what she calls “a tactical approach” that includes “stocking strategies that incorporate those extended lead times.”

Before the COVID pandemic hit in 2020, Festo functioned with 45-day lead times to receive its goods from Germany, where most of its products are manufactured.

“Now 75 to 80 days is pretty consistent,” Harper-Gage said, noting that lead times had peaked at about 100 days. That has a ripple effect for Festo’s U.S. customers.

“We’ve adjusted our lead times to incorporate those 80 days.”

She noted cautiously that things may be slowly improving.

“Key pockets of our backlog are improving and becoming more stable,” she said. “We’re seeing some reduction of that backlog in some of our other products, getting back to a more stable production and delivery cycle.”

War in Ukraine

Despite the progress that Festo sees, the crisis in Europe that began with Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine on Feb. 24 is adding to the supply chain worries.

“What really concerns me now is the crisis in the Ukraine,” Harper-Gage said. “Will it have a ripple effect globally on supply chains? Whether it’s in the air carrier side of things or whether it’s in the actual material side of things, I think we’re bracing for an impact.”

Supply Chain Quarterly, a journal of the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals, recently reported that “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is striking a blow to already battered global supply chains, and North American logistics professionals say the ripple effects will be felt here at home in the weeks to come.”

Reshoring the supply chain

The logjam has driven many companies to consider more local alternatives to the sources of materials they need to make their products.

“We’re continuing to look for local sources,” Harper-Gage said.

The National Fluid Power Association, in one of its recent Business Intelligence Surveys, reported that member companies are looking for alternative supply sources.

“There’s a lot of activity in trying to diversify their sourcing, broaden their supplier base,” Pete Alles, vice president of member services and operations for NFPA, told Fluid Power Journal.

“A lot of people are talking about developing new sources.” He quoted one respondent to a recent survey who said he’s “reshoring all my China-based product.”

“Others are focusing on trying to buy domestically or closer to the United States. That shows up a lot,” Alles said.

He said the supply chain is the top concern of the fluid power companies NFPA has surveyed.

“It continues to be an ongoing concern,” Alles said. “A lot of companies are struggling with backlog and trying to fulfill, and difficulties with sourcing materials and product. That’s just an ongoing phenomenon right now. It’s expected to continue for awhile.”

Related to the supply chain worries is what Alles called “demand amplification,” in which customers order much more than they really need from several suppliers. When they have sufficient supplies, the customers cancel the order or parts of it.

“One of the concerns is that customers are placing extra orders and kind of panic buying,” Alles said. “You might have potentially an artificial level of demand that comes back to bite you in six months or a year, when you find you have cancelations.”

Electronics shortages

The supply chain crisis has caused the most problems for companies that incorporate electronics into their products. The shortage of chips and electronic components has some companies scrambling to fill orders and find alternative supply sources.

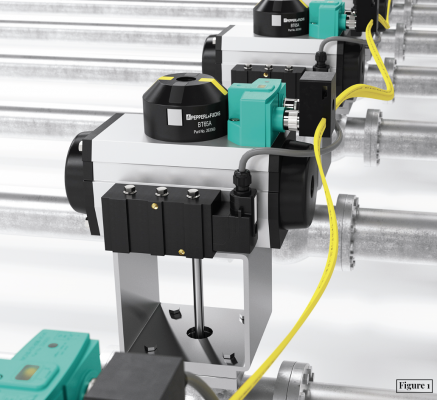

“Globally we see across the board there’s a shortage of electronic components,” Kevin Vanderslice, director of sales at ifm efector, told Fluid Power Journal. “You see most of this throughout the automotive industry, and that just trickles down to sensors, controls, and smart hydraulic valves. You can’t get the necessary microcontrollers or transistors.”

The impact has led ifm efector to put more energy and resources into obtaining raw materials, Vanderslice said.

“Maybe you have five or six people, like we did, contacting suppliers on a regular basis. Now over 50 give that constant contact.”

He said the production lines at ifm efector, which primarily makes sensors and controllers, have been working three shifts, seven days a week.

“You also have to be prepared that when you do get the product, and the product does show up, that you can fulfill your customers’ wishes and demands,” Vanderslice said.

The company is spending more resources on the supply chain shortages.

“Not only are we constantly contacting our suppliers, we’re actually three times a day scanning the broker market to see what components are out there,” he said. “It’s a lot of extra work and time and cost, because if you have to go out into the broker market to find product, you could be paying 10 to 20 times the cost for a certain component.”

He said fulfillment is not at normal levels.

“Our fulfillment was 90.7%, and we increased it to 94.2% in the month of January. That’s unbelievable in these unprecedented times. But it’s still not the 97% that we’ve done for a number of years,” he said.

European suppliers

Supply chain problems can depend on where suppliers are located. Wandfluh America, which makes hydraulic and electronic systems and components, has seen fewer supply chain problems because its suppliers are in Europe, said Gary Gotting, president of Wandfluh America.

“We happen to be in a pretty good position because we get our products coming in from Europe, from Switzerland,” Gotting told Fluid Power Journal. “So from a supply chain point of view, Europe has a lot more opportunity to go shopping for raw materials.”

He said the company has used many long-term suppliers, and those relationships have helped Wandfluh avoid some of the supply chain headaches others are experiencing.

“Buyers, planners, [and] production people have been entrenched with the same suppliers for decades,” he said. “We have a very good relationship, and the relationship is really helping in these times when everybody’s screaming for the same materials.”

He said Wandfluh has not seen supply chain problems trickle down to fulfillment.

“Our worst delivery right now is 12 weeks for any product we have in the portfolio,” Gotting said. “That’s a testament to our logistics and our supply chain from Europe. Some of our major competitors are out to 42, 48, 52 weeks.”

Gotting said another reason Wandfluh is not seeing extreme lead times is transportation.

“Everything we have coming from Europe comes in air freight,” he said. “Getting it from the airport to us in Chicago, that’s becoming longer.”

Though Wandfluh experiences 12-week delivery times, their backlog has grown in the past two years, Gotting said, because customers ran down their inventories and now have pent-up demand.

“Our backlog’s increased somewhere between 50 and 60% since COVID,” he said. “Now [customers are] starting to buy, and they’re starting to schedule serial production. They’ve started to schedule out to match what we can deliver. So we’re seeing a lot of backlog grow from that.”

Whether Wandfluh’s good fortunes with its European suppliers will be affected by the war in Ukraine remains to be seen.

Labor crisis

But raw-material deficits aren’t the only ones affecting fluid power companies. Worker shortages and difficulty hiring also affect how quickly companies can fill orders.

Gotting said Wandfluh America, a small company with 16 employees in its U.S. facility near Chicago, has had trouble filling jobs for higher skilled labor such as machining and finishing processes.

“Every one of our divisions around the world has the same kinds of issues,” Gotting said. “We can’t find the right kind of people, the skilled labor.”

Even when Wandfluh finds new workers, they often don’t stay on the job, he said.

“We’ve had some candidates walk through the door. They look great, they sound great. We’ve even started a couple. And they’re there for a week, and literally they’ll turn around and say, ‘This is too much like hard work.’ A forty-hour week seems to be something that’s becoming alien to some of these people who walk through the door.”

Aggressive Hydraulics’ Paul Johnson said his company has experienced long-term difficulties filling open positions.

“That’s been a problem for the past few years, and it’s worse now than ever before,” he said.

“We have open positions for every trade function in the plant. To find the right person is taking longer than we’ve experienced in the past.”