The Real Value Of Hydraulic Circuit Diagrams

Like many readers of this Journal, I’m regularly involved in troubleshooting problems with hydraulic equipment. When in these situations, there are two things I always do before reaching for any of my diagnostic tools. The first is to conduct a visual inspection of the hydraulic system, checking all the obvious things that could cause the problem in question (always check the easy things first). The second is to request a circuit diagram.

There are four main types of diagrams that may be used to describe all or part of a hydraulic system: block, cutaway, pictorial, and graphical.

- Block Diagrams show the components of a circuit as blocks joined by lines, which indicate connections and/or interactions.

- Cutaway Diagrams show the internal construction of the components and flow paths. Because these diagrams typically use colors, shades, or patterns in the lines and passages, they are very effective at illustrating different flow and pressure conditions. This makes them ideal for training purposes.

- Pictorial Diagrams are often used to show a system’s piping arrangement. The components are seen externally and are usually in a close reproduction of their actual shapes in scaled sizes. This aids in component recognition and identification.

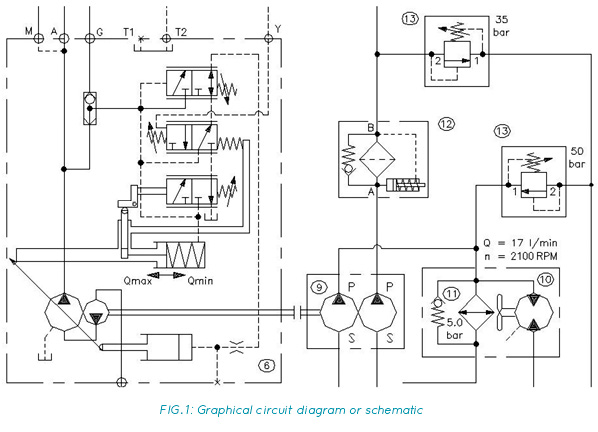

- Graphical Diagrams, a.k.a. schematics, are the shorthand system of the fluid power industry (Fig. 1). They comprise simple, geometric symbols, drawn to ANSI or ISO standards, that represent the components, their controls and connections.

Graphical diagrams are preferred for troubleshooting purposes. A graphical circuit diagram or schematic is a “road map” of the hydraulic system, and to a technician skilled in reading and interpreting them, is a valuable aid in identifying possible causes of a problem. And this can save a lot of time and money in a troubleshooting situation.

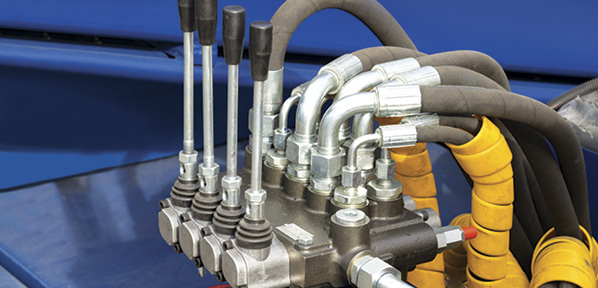

If a schematic diagram is not available, the technician must physically trace the hydraulic circuit and identify its components in order to isolate possible causes of the problem. This can be a time-consuming process, depending on the complexity of the system. Worse still, if the circuit contains a valve manifold, the manifold may have to be removed and dismantled—just to establish what it’s supposed to do. Reason being, if the function of a component within a system is not known, it can be difficult to discount it as a possible cause of the problem. Schematic diagrams eliminate the need to reverse engineer the hydraulic system.

Where Are All The Hydraulic Circuit Diagrams?

As most experienced hydraulic technicians know, there’s usually a better than even chance that a schematic diagram will not be available for the machine they’ve been called in to troubleshoot. This is unlikely to bother the technician, though, because it is the machine owner who usually pays for its absence through prolonged service calls and increased downtime.

Where do all the hydraulic schematic diagrams go? They get lost or misplaced, they don’t get transferred to the new owner when a used machine is traded, and in some cases, they may not be issued to the machine owner at all. Why? Because generally speaking, hydraulic equipment owners don’t place a lot of value on them.

So if you’re responsible for the maintenance of hydraulic equipment and you don’t have schematic diagrams for all your existing machines, try to obtain them before you need them. The nominal cost involved could save you a lot of money in the long run. In the case of a mass-produced machine, the hydraulic circuit diagram should be available from the equipment manufacturer on request.

If the machine is custom-built and the designer unknown, it may be necessary to have the circuit drawn from scratch. A fluid power engineer or your preferred hydraulics supplier could provide this service. When procuring schematic diagrams, request both electronic (.dwg or .dxf preferably) and hard copy. Having an electronic copy makes it easier to update the drawing if the circuit is modified at any time. And always ensure that you are issued schematic diagrams for any additional hydraulic machines you acquire.

And if you design and build hydraulic machines, do your customers a big favor and make sure you give them an accurate schematic diagram with every machine they buy. While this may be viewed by some as making life easier for a competitor down the track, such narrow-minded thinking only serves to diminish the overall professionalism of our industry.

I really want to know about hydraulic system. And I hope this would help me