Don’t Follow The Crowd, Mount Your Hydraulic Pumps…For Life

By Brendan Casey

An essential requirement for the optimum performance and service life of a hydraulic pump is that its pumping chambers fill freely and completely during intake. So if getting maximum pump life is your primary concern—and it should be—then anything that makes the free and complete filling of the pump’s chambers more difficult to achieve ought to be avoided.

Suction strainers and most other forms of inlet filtration is a common culprit. With rare exceptions, a suction strainer has no place in a properly designed and properly maintained hydraulic system.

But when you take a position against the majority, there will by many who disagree with you. And so I regularly hear from folks who feel they need to explain to me why their hydraulic system is different and why they have no alternative but to use this pump-killing device.

I prefer not to debate the point with people who’ve convinced themselves of the merits of suction strainers—or in some cases, use them as a substitute for proper design and/or maintenance. I refer them to the pump manufacturer’s recommendation instead. Here’s an excerpt from a Rexroth Hydraulics manual1 that dates back to 1979:

“The advantages of suction filtration are strongly outweighed by the disadvantage of the pressure drop created by the element… Any benefit the suction filter offers by keeping contamination out of the pump, is offset by the possibility of damaging the pump because of cavitation…

“Another major disadvantage of the suction strainer is that it is located inside the oil reservoir which makes it inconvenient to service. It is for this reason many suction strainers in hydraulic systems go unserviced until they starve the pump and cause cavitation damage.

“Due to these disadvantages… filtration at the inlet of the pump is specifically not recommended.” (The use of italics is theirs.)

It speaks volumes about the hydraulics industry, that this 30-year-old advice from a leading hydraulic pump manufacturer is still widely ignored today.

But a suction strainer isn’t the only “engineered-in” barrier to the free and complete filling of the pump. Another is mounting the pump above the tank or more precisely, above minimum oil level. In other words, making the pump “lift” the oil into its intake.

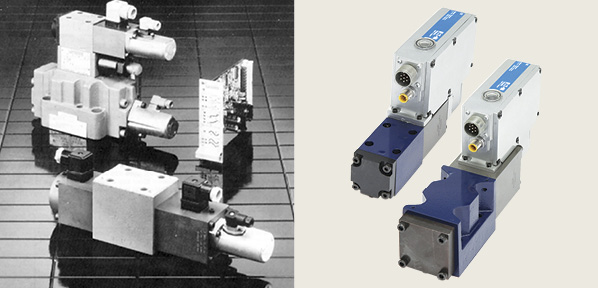

According to most manufacturers, mounting the pump above minimum oil level is an “approved” mounting position for many pump designs. “Approved” meaning, the manufacturer says it’s OK to do it. But “approved” does not mean it maximizes pump service life. Because making the pump lift its oil does the opposite. This is particularly true for piston and vane pumps, which due to their design do not cope well with vacuum-induced forces.

Pump inlet conditions also affect noise and heat load. When exposed to atmospheric pressure at room temperature, mineral hydraulic oil contains between 6% and 12% of dissolved air by volume. If the pressure on the oil is reduced to less than atmospheric pressure—due to a restriction in the pump intake or required lift—this air expands and becomes a higher percentage of the volume.

These expanding gas bubbles at the pump inlet collapse as the pumping chamber is exposed to system pressure (gaseous cavitation). The result is heat generation and noise. The larger the air bubble, the higher the noise level and heat generated. If the absolute pressure at the pump intake continues to fall (higher vacuum), the oil can start to change state from a liquid to a gas—known as vaporous cavitation.

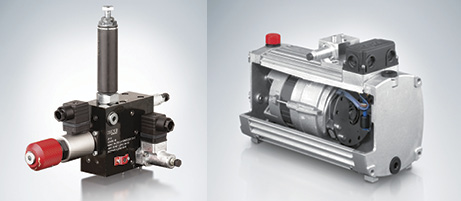

For these reasons, the perfect pump inlet condition is 100 percent boost. Meaning, ideally, you want the pump inlet to be supercharged under all operating conditions.

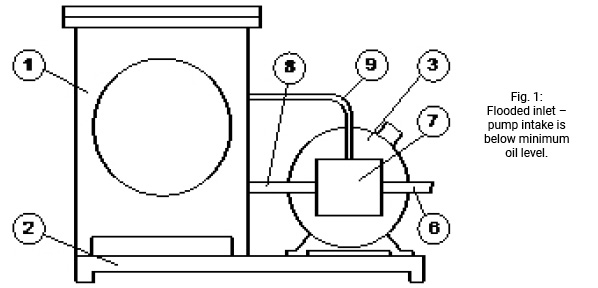

While supercharging the pump inlet is not practical in most applications, there is virtually no excuse for not having a flooded inlet. A flooded inlet means there’s a head of oil above the pump. In other words, the pump is mounted in such a way that its intake is below minimum oil level (Fig. 1).

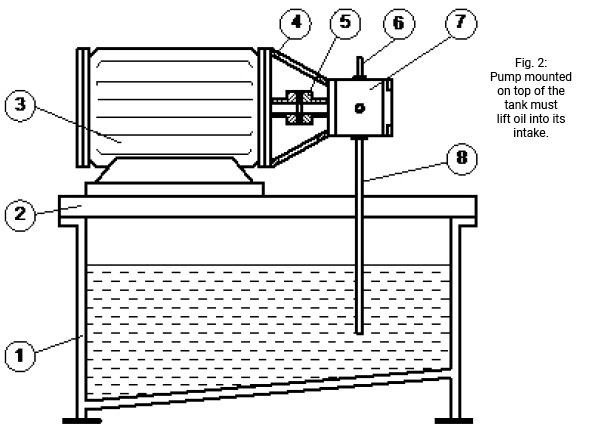

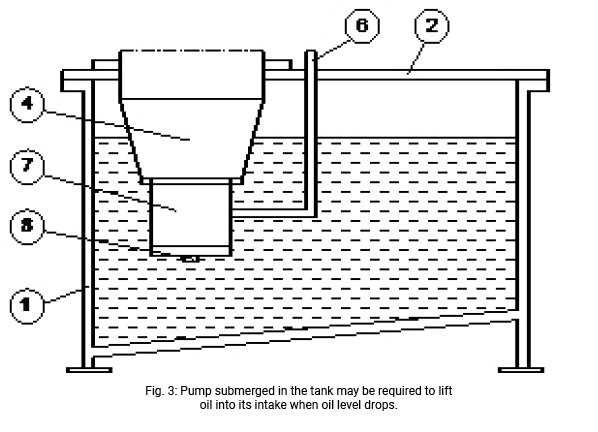

In the case of industrial power units, this rules out mounting the pump on top of the tank (Fig. 2). And in most cases, it will rule out mounting the pump inside the tank with the electric motor mounted vertically (Fig. 3), unless the pump is submerged to a depth where its inlet port is below minimum oil level (without the need to install a drop tube on the intake).

Besides making the pump lift its oil, both these mounting positions (Figs. 2 and 3) make maintenance extremely difficult. Pump inside the tank being the worst. But unfortunately (for the owners of this equipment), mounting the pump inside the tank has almost become standard practice for electric power units, because it’s a cheap and easy method of construction.

So if you design hydraulic equipment, mount the hydraulic pump for life. Think twice before installing a suction strainer and ensure the pump has a flooded inlet. You’ll be doing your customer—and your machine’s reliability—a big favor.

Brendan Casey is the founder of HydraulicSupermarket.com and the author of Insider Secrets to Hydraulics, Preventing Hydraulic Failures, Hydraulics Made Easy and Advanced Hydraulic Control. A fluid power specialist with an MBA, he has more than 20 years experience in the design, maintenance, and repair of mobile and industrial hydraulic equipment. Visit his Web site: www.HydraulicSupermarket.com.

Reference

1Frankenfield, T. C. 1979, Using Industrial Hydraulics, Hydraulics & Pneumatics Magazine, Cleveland, p. 10-31.

Excellent post. I particularly like the quotes from Tom Frankenfield’s manual.

It surprising to me how common inlet filters are in new installations for variable displacement piston pumps. Variable displacement pumps have to accelerate the oil column every time they go on stroke, not just when starting the prime mover. This calculation is not always taken into account.

Very helpful post, I’ve always supercharged my inlets but these days I prefer flooding the inlet.

As for the suction strainer, I have never imagined it could restrict oil flow in that manner. Overall, a very good article.