Going Electric? SHA is the Dynamic Choice

By Carl Richter, Vice President and General Manager, Kyntronics

In recent years, with the push in many industries to switch to all-electric machines, electromechanical actuator (EMA) companies have gone after the hydraulics market. This can cause confusion and dissatisfaction for two reasons: EMA applications engineers may not understand the hydraulics industry and are challenged to properly apply an optimal EMA product. Further, hydraulics engineers may not be fluent enough with EMA technology to know what questions to ask. Both situations have led to premature product failures and dissatisfied customers.

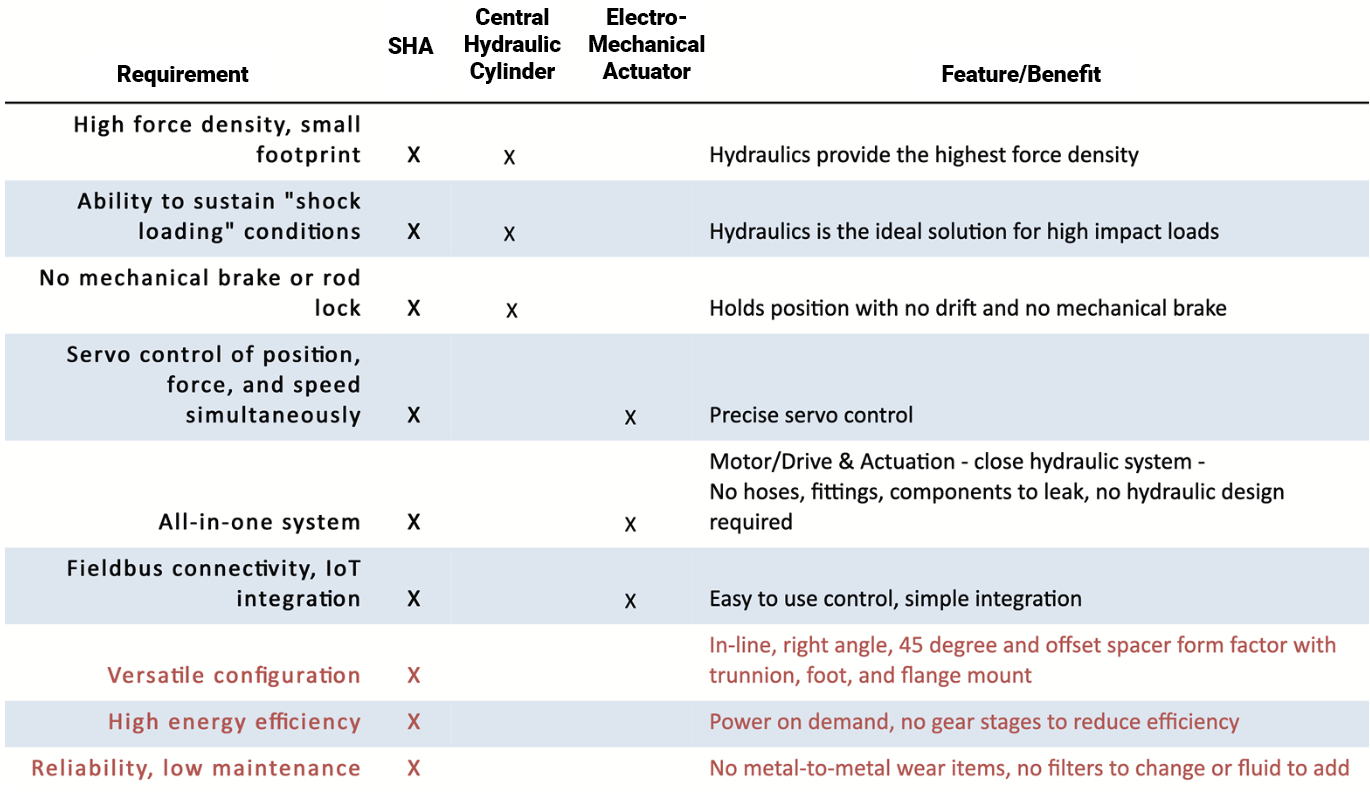

There have been two choices for powerful, accurate actuation: a central hydraulic system or an EMA. But a third technology combines the best features of both and is the choice for “going electric”: the smart hydraulic actuator (SHA).

Today many of the EMAs that tried to replace hydraulics are failing due to several factors, including not fully understanding the machine and the applied hydraulics.

Hydraulics is tough, powerful, and often plows through mechanical “inefficiencies.” Hydraulics encourages impact and shock loading, and it has the capability to compensate for some side loading. EMAs run away from these; they cannot handle shock loading and do no warranty for side-loading mountings.

EMAs promote a certain static IP rating. Once the EMA starts moving, the IP rating is no longer valid. With the roller screw moving, it sucks in whatever fluid is moving around the machine and causes premature nonwarranty failures.

Also, some advertised EMA efficiencies are inaccurate or incomplete and sometimes based on ideal or theoretical calculations. Kyntronics’ tests show the SHA to be 40% to 50% more efficient because of its smaller motor and drive. The roller screw actuator’s total efficiency is sometimes not promoted.

Because hydraulics and electric are different technologies, they speak different languages and use different symbols. Hydraulics symbols look like hieroglyphics to an electric company, which likely will not understand the control dynamics. Closed loop servo control responds much differently than a flow control valve. The closed loop servo will respond to machine binding issues and resonances, which likely will not translate to smooth motion. The hydraulics are powerful and will be smooth with a simple flow control.

It is also important to understand the true life of an EMA so there are not sudden failure surprises.

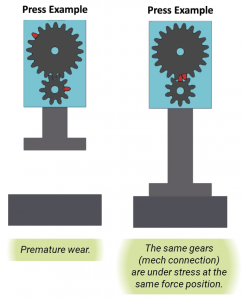

Hydraulics has many advantages over EMA technology. A hydraulic cylinder requires no brakes, and its footprint is much smaller. Impact loads along with side loading are much more robust with hydraulics. EMAs require preloading for accurate solutions, leading to reduced efficiencies. EMAs require maintenance, need to be kept cool, and need to stay greased. They have continuous metal-to-metal contact that causes reliability issues. In a failure, if there’s been no maintenance, the warranty is voided, and the customer’s operation can go down, causing frustration. When looking at larger loads, e.g., greater than 8klbf, EMAs can get large and expensive, and reliability decreases. Especially when pressing a certain load at the same position over and over, EMAs can fail prematurely. Because hydraulics is just pressure and moving fluid, there are no major metal-to-metal wear parts. With hydraulics, the retract speeds are faster than the extend speeds, which is a cycle-time benefit. EMAs need to oversize to properly compensate. It is also difficult and expensive for an EMA to perform accurate force control; for an SHA or hydraulic actuator, it is done with simply a pressure sensor (F = A & psi).

Hydraulics has many advantages over EMA technology. A hydraulic cylinder requires no brakes, and its footprint is much smaller. Impact loads along with side loading are much more robust with hydraulics. EMAs require preloading for accurate solutions, leading to reduced efficiencies. EMAs require maintenance, need to be kept cool, and need to stay greased. They have continuous metal-to-metal contact that causes reliability issues. In a failure, if there’s been no maintenance, the warranty is voided, and the customer’s operation can go down, causing frustration. When looking at larger loads, e.g., greater than 8klbf, EMAs can get large and expensive, and reliability decreases. Especially when pressing a certain load at the same position over and over, EMAs can fail prematurely. Because hydraulics is just pressure and moving fluid, there are no major metal-to-metal wear parts. With hydraulics, the retract speeds are faster than the extend speeds, which is a cycle-time benefit. EMAs need to oversize to properly compensate. It is also difficult and expensive for an EMA to perform accurate force control; for an SHA or hydraulic actuator, it is done with simply a pressure sensor (F = A & psi).

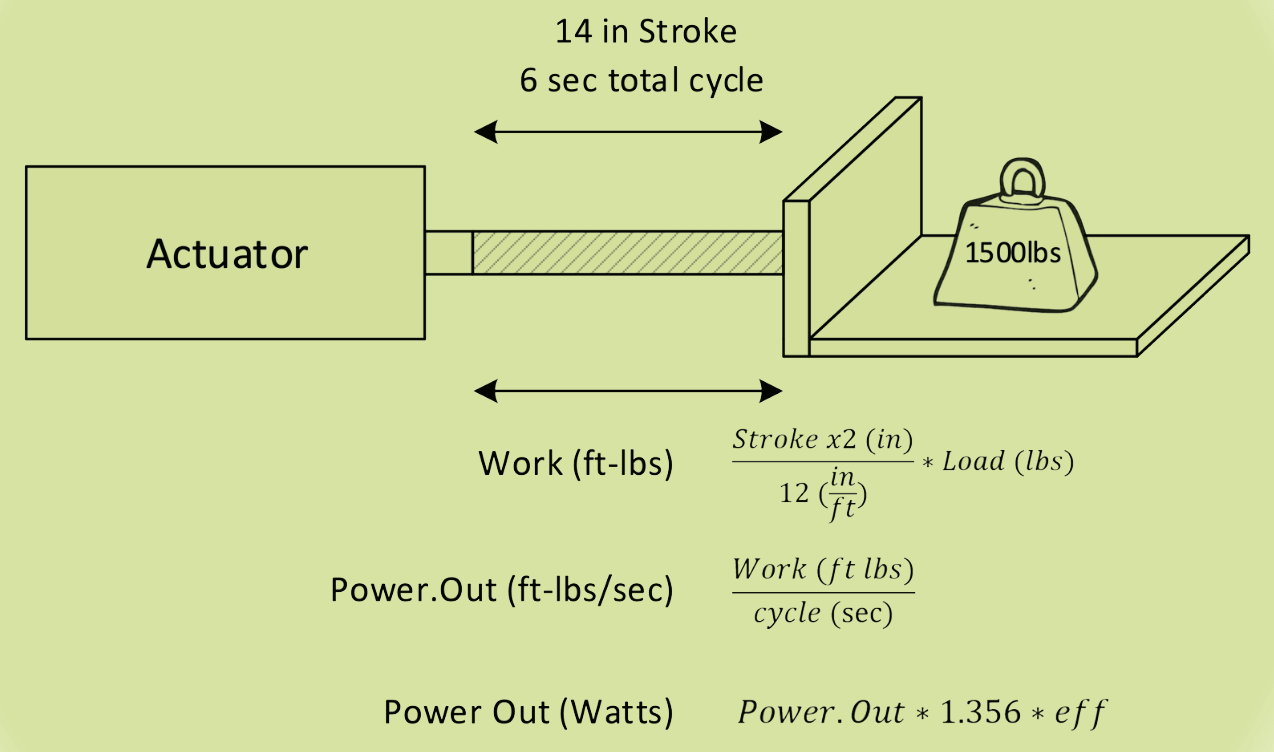

When considering moving to an all-electric solution, be as educated as possible. Understand the machine’s existing needs and its possible future needs (speed, force, and duty cycle). Understand what your reliability is today and set those expectations with your actuation supplier. Challenge the EMA supplier to provide reliability data for IP ratings when in motion, required maintenance, and inertia calculations, including the machine. Because hydraulics is so powerful, in most instances inertia is not an issue. Especially for the higher loads, the overall EMA actuator and machine inertia may need to be taken into consideration. An easy test is to understand the horsepower running the cylinders (load over distance and time). Does the EMA motor HP make sense? Many times, it does not. Ask for the HP calculations (moving x lbf, over a distance in y seconds).

Another quick test is to compare the total EMA’s motor power to that of the hydraulic power unit. Usually the HPU is oversized. But if the EMA’s total power is over or significantly under, ask questions. Power is power, there is no getting around physics.

Kyntronics makes both EMAs and hydraulic actuators. But an alternative path is to consider the Kyntronics SHA for an all-electric solution. The SHA is an all-inclusive servo hydraulic solution that is completely sealed, so there are no leaks. It takes advantage of the benefits of hydraulics while solving EMA issues. Because of the significant demand for the SHA, coupled with the diminishing demand for the EMA, the SHA is the future for Kyntronics and potentially the future for many companies’ actuation needs.

For more information, visit www.kyntronics.com/products/smart-hydraulic-actuator-sha.